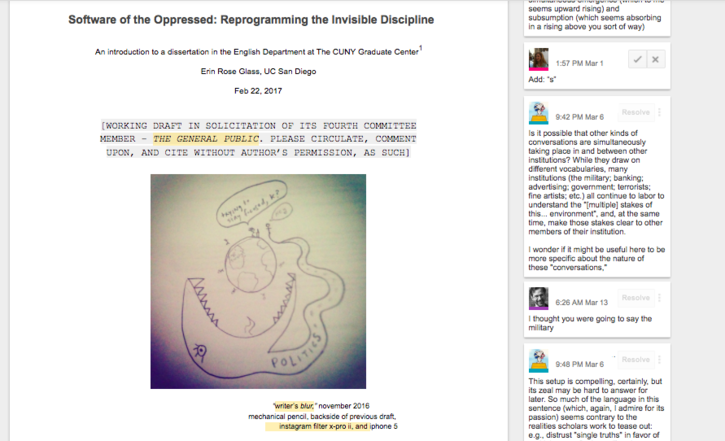

In February 2017, I began #SocialDiss, a project in which I aimed to post draft chapters of my dissertation on different commenting platform in solicitation of public peer review. It was inspired by my earlier work on Social Paper, a non-proprietary platform for socializing student writing and feedback. (Read the manifesto here.)

Below are links to some of the reflections on the process as well as the socialized drafts. You can also check out the twitter thread here. I am currently working on writing a critical evaluation of the process.

I am honored to have received the 2018 Emerging Open Scholarship Award from the Canadian Social Knowledge Institute for this project.

Working on something similar? I’d love to hear from you.

To what extent can the general public participate in and benefit from the production of a dissertation? How might the private and anxiety-ridden processes of education be transformed into a public good and social joy? Are the imperfect artifacts of learning to be hidden and disposed of as shameful waste, or might they provide fertile soil for the cultivation of a global learning community? Could the form of the dissertation itself blossom into something more vibrant and responsive to today’s world in the process? (Read more)

To what extent can the general public participate in and benefit from the production of a dissertation? How might the private and anxiety-ridden processes of education be transformed into a public good and social joy? Are the imperfect artifacts of learning to be hidden and disposed of as shameful waste, or might they provide fertile soil for the cultivation of a global learning community? Could the form of the dissertation itself blossom into something more vibrant and responsive to today’s world in the process? (Read more)

-

Welcome to #SocialDiss and the Cyborg University (MLA Humanities Commons)

-

Draft of (now discarded) introduction (Google Docs)

-

Draft of (now discarded) introduction (Social Paper)

About four months ago, I launched #SocialDiss, an experimental project in which I’ve committed to “socializing” every chapter of my dissertation draft on a variety of publishing platforms. In late February, I posted the working introduction to a public Google Doc, and over the next few weeks, announced its presence on Twitter, Facebook and a few emails to friends and colleagues.

I wasn’t sure if anyone would actually engage with it. I was halfway hoping no one would.

If our networked tools for sharing knowledge are free, far reaching, and fast, does it matter who owns and governs them? I’m posting the draft of a chapter of my dissertation on the Humanities Commons in support of the belief that the infrastructure of knowledge production is in fact as important as the content of knowledge itself. Though freely-available virtual spaces such as Facebook, Google Docs, and Academia.edu enable democratic, open, and collaborative forms of knowledge production, their use simultaneously contributes to the power and intelligence of corporations that deny public understanding and oversight of their activities.

-

Draft Chapter: Alienated intelligence: The private interests of the ‘World Brain’ (MLA Humanities Commons – CommentPress Website)

I adore this painting, ‘The Bus” by Scott Listfield. Somebody buy it! Image linked to gallery.

Since the turn of the 21st century, a wealth of terms have emerged or taken on new life that describe the diverse ways research, teaching, and the university itself are adopting new technologies and technological practices. Some of these terms call overt attention to technology, such as “the digital humanities,” “digital scholarship,” “digital pedagogy,” “digital learning”, “e-learning,” “educational technology,” “escholarship,” “digital rhetoric,” “the digital university,” “the virtual university,” “networked participatory scholarship,” and so forth. Other terms, while less explicit in their relation to technological practice, still describe academic practices that have come to depend equally on recent technological advances in the ability to cheaply and rapidly share or analyze information, such as “open access,” “data science,” “participatory learning,” “scholarly communication,” or “the information-rich university.” (Read more.)

- Writing in the Age of Alienated Intelligence: The Techno-rhetorical Situation of the Cyborg University (Academia.edu)

It is an interesting time to be writing, especially within the university. Professors, brought to the brink of “hysteria” from grading poorly-wrought student papers post poetic odes and launch social media accounts bemoaning what they see as an intellectual tragedy of national proportion. Students, in cheerful agreement about the quality of their work, demonstrate mastery in digital communication through networked boastings, viral tutorials, crowd-sourced requests, and convivial complaints related to the practice of “bullshitting” the student paper …